The sunken Dutch parterre is but a corner of 17 acres of Victorian gardens at Lyme Park. Originally a Tudor house, Lyme Park was transformed into a Palladian mansion by the celebrated Venetian architect Leoni. [/caption]

I MAGINE THE PRISTINE WATERS of Cumbria’s Lake District outlined with campsites, holiday cottages and caravans, bristling with speedboats and water-skiers. Imagine a multistory car park where Fenton House stood, or Powis Castle carved into timeshare flats.

It is almost impossible to imagine England, Wales and Northern Ireland without the protection of the National Trust (NT). Certainly there would be far less for us to appreciate and to connect us to the past if this not-for-profit organization had not been in existence for these past 112 years overseeing the natural beauty and history of these countries.

The National Trust has been the guardian and protector of such diversity as castles, houses and gardens, museums, factories and mills, villages, dovecotes, medieval barns, mills, pubs, lighthouses, nature reserves, some 700 miles of coastline and more than 600,000 acres of countryside. These properties have been preserved for the enjoyment of everyone for as long as life exists as we know it.

Octavia Hill, Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley and Robert Hunter founded the National Trust in 1895. They could scarcely have comprehended the far-reaching and timely themes of environmental protection, cultural preservation and resource conservation that engages the NT today.

Hill, an extraordinary figure in Victorian England, was dedicated to improving housing and urban open spaces for the poor. She saw that “the need of quiet, the need of air, the need of exercise, and the sight of the sky and of things growing seem human needs common to all men.” Rawnsley was a strong advocate all his life for the preservation of his cherished Lake District, where he was vicar of Low Wray Church and later Crosthwaite, near Keswick. Hunter was a successful solicitor and civil servant who had an illustrious career working with the Post Office.

In 1884 Hill asked Hunter to help save the garden at Sayes Court, which was located next to the naval dockyard in Deptford in East London. Hill wanted the garden to be made public for the enjoyment of the poor people of the neighborhood, who had no country homes or access to green spaces. Sayes Court had been the home of the noted diarist John Evelyn and his wife in the mid-17th century, and it was Evelyn who had transformed the garden into a place of beauty.

Toward the end of the 19th century, the owner of Sayes Court wanted to give the property to the nation, but there was no organization in existence to accept the gift. It was this void that led to the idea of a National Trust to help care for future donated properties.

While the Alfriston Clergy House was the first building purchased by the National Trust in 1896 (for the enormous sum of £10), Rawnsley, Hill and Hunter purchased the National Trust’s first tract of land, Brandelhow Park, on the shore of Derwent Water in the Lake District in 1904 to prevent a large housing development from being built there.

The campaign to raise funds for the purchase of Brandel-how received wide support, with donations coming in from far and wide. They included contributions from Princess Louise, a daughter of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, as well as factory workers in the industrial Midlands. Even people who would never get to see the Lake District themselves sent in small amounts of money to help protect the land for others.

T ODAY BRANDELHOW PARK remains a pretty and peaceful oasis providing an excellent protected habitat for the local wildlife, which includes deer, red squirrels and herons. Canon Rawnsley became the first secretary of the National Trust and remained its honorary secretary until his death in 1920.

Beatrix Potter’s father Rupert became the National Trust’s first life member. Beatrix, the writer and illustrator of such children’s classics as The Tale of Peter Rabbit in 1900 and The Tailor of Gloucester in 1902, used the income from her books to support the Trust’s work in the Lake District. She even managed some of the farms in the area on behalf of the Trust, and is recorded as saying that “the Trust is a noble thing, and humanly speaking immortal. There are some silly mortals connected with it, but they will pass.”

In 1907 Hunter, who had drafted a large number of successful legislative bills for the Post Office, drafted an act ensuring that most of the properties under the National Trust are held in perpetuity to guarantee their future protection. (He was later thanked for his legislative efforts with a knighthood.) The National Trust Act of 1907 allowed the Trust to: (1) declare land “inalienable” so that the Trust could commit itself to look after the land forever without fear of it being taken away; (2) promote permanent preservation for the benefit of the nation of lands of beauty or historic interest; and (3) set up a council to bring together people elected by the Trust’s members, and experts appointed by other organizations with an interest in the Trust’s work.

A SECONDNATIONAL TRUST ACT WAS PASSED in 1937 permitting owners to transfer their homes to the Trust yet to continue to live in them. Blickling Hall in Norfolk became the first house to be accepted on this basis, and the arrangement has been in effect from 1940 to the present. Sissinghurst Castle in Kent, where writer Vita Sackville-West and her husband Harold Nicolson lived for many years, has a similar arrangement. In 1967 the castle and gardens were left to the Trust. Today Juliet Nicholson, the granddaughter of Sackville-West and Nicolson and the author of The Perfect Summer: England 1911, Just Before the Storm (see British Heritage , January 2008, P. 43), and her family live in one wing of the house. An arrangement like this was made even more enticing in 1945 when the British government began allowing gifts of properties to be used to relieve death taxes.

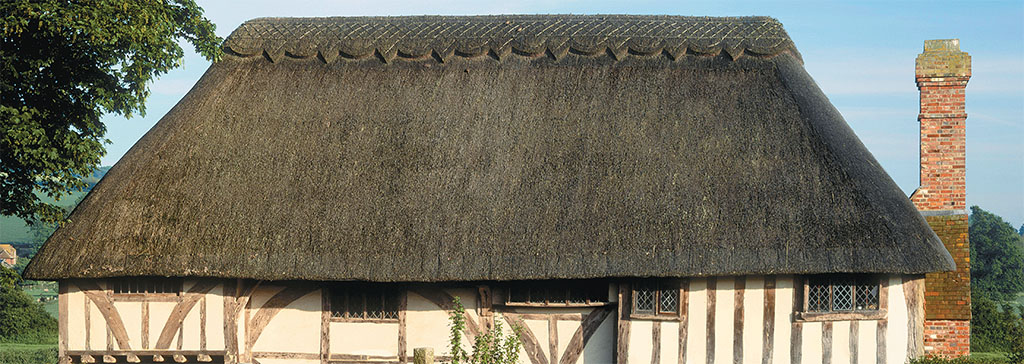

Historic buildings now under the protection of the National Trust include Castle Coole in County Fermanagh in Northern Ireland, an elegant 18th-century mansion; Lyme Park in Cheshire, a Tudor house that was transformed in the 18th century; and Powis Castle in Wales, built in 1200 high on a rock above its terraced garden.

The houses of famous people give visitors a closer look at these individuals and their times. Wordsworth House in the village of Cockermouth in the Lake District offers a glimpse of the poet’s family life, as actors in costume portray what it was like to live in this area in 1770. Spend a day at Winston Churchill’s beloved Chartwell, his country home for decades in Westerham in Kent, and the political man as well as the artist and family patriarch come alive before your eyes.

Bateman’s, the Jacobean structure in East Sussex, was home to the writer Rudyard Kipling, and the house inspires visitors to read and reread his books and poems. The Red House, a deep-red brick building, was specially designed for William Morris and his bride, who lived there for five years after their wedding. In this house, Morris started the well-known Arts and Crafts Movement.

More recent acquisitions and ones that continue to show the range of interest of the National Trust are the boyhood homes in Liverpool of two of the four Beatles. Today visitors can tour the council estate house where Paul McCartney moved with his family in 1955 as well as the 1930s house where John Lennon went to live with his aunt and uncle in 1945 when he was 5 years old. The Trust focuses on the smallest details while restoring homes so that they retain the essence of the people who once lived in them, as well as the aura of their times.

To many the National Trust is known for the outstanding collection of gardens under its jurisdiction, which together encompass about 400 years of gardening history. More than 450 skilled gardeners and over 1,500 volunteers are retained by the Trust to keep these gardens well maintained.

Among the more famous gardens are Trelissick in Cornwall, with its exotic plants on different levels and its views down to Falmouth and the sea beyond; and Hidcote Manor Garden, Gloucestershire, with its series of outdoor “rooms,” each with individual characteristics. Lesser known treasures include Greys Court, a series of walled gardens formed by the remains of a 14th-century medieval house in Oxfordshire; and Colby Woodland Gardens, which has one of the finest collections of rhododendrons and azaleas in Wales.

In 1998 the Trust was able to buy the more than 4,000 acres that made up the Hafod y Llan estate, consisting of three hill farms in the heart of Snowdonia National Park in Wales. The Snowdonia appeal was launched by the actor Sir Anthony Hopkins, who also helped the Trust to acquire part of Snowdonia itself.

A MONG THE TRUST’s MANY unique properties is Patterson’s Spade Mill, one of the last water-driven spade mills in Northern Ireland. Founded in 1919 to produce a range of implements from simple tools to heavy-duty spades, it was run as a family business for more than 70 years, but closed in 1990. The Trust acquired the property in 1992 with all its machinery and fittings intact, and reopened the mill in 1994, forging spades once again.

[caption align="alignleft" width="1024"]

One of the NT’s most popular garden visits is Sissinghurst Castle Garden. A dozen miles east of Tunbridge Wells, the garden was the impassioned creation of Vita Sackville-West, who lived there for many years. [/caption]

‘The Trust not only amasses properties, it also cares deeply that its holdings are preserved to reflect the times that they represent’

The 14th-century Alfriston Clergy House in the pretty Cuckmere Valley of the East Sussex weald was the first property acquired by the National Trust, in 1896. [/caption]

THE NATIONAL TRUST PRESENTLY CARES for more than 612,000 acres of forests, farmland, downs, moorland, fens, beaches and islands in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. It preserves and conserves about 700 miles of coastline.

Every year, the NT welcomes some 12 million visitors to its more than 350 historic houses, castles gardens and mills open to the public. Completely independent of the Government, the Trust is a charitable organization, with 3.5 million members and 43,000 volunteers.

The National Trust’s central headquarters are in Swindon, Wiltshire, in a cutting-edge remake of a Victorian engineering foundry named Heelis. The building is open to the public seven days a week with a creative café and well-stocked National Trust gift shop. Public tours are given every Friday.

Only footsteps from the two small rooms that the Trust occupied in Victoria Street in 1907, the Blewcoat School on London’s Caxton Street is a charming, small red-brick building that was a school for the poor in the 18th century. Now a Trust property, it serves as gift shop with many items obtainable only from the National Trust. The school is easily recognized from the figure of a school child dressed in blue perched over the front door.

It would take years to visit all the National Trust properties and take full advantage of its brilliant walking opportunities, such as the six-mile hike around Upper Wharfedale in the Yorkshire Dales; or the walk around the Stackpole Estate through the spectacular scenery of Pembrokeshire National Park in southern Wales.

The Trust not only amasses properties, it also cares deeply that its holdings are preserved and maintained so as to reflect the times that they represent. In 2002 the Trust went to the rescue of the wild golden daffodils made famous by William Wordsworth in 1804 when he and his sister Dorothy were walking on the shores of Ullswater in the Lake District. Wordsworth wrote:

I wandered lonely as a cloud that floats on high o’er vales and hills, When all at once I saw a crowd, A host of golden daffodils.

Those golden daffodils were threatened with extinction by another species growing nearby that would soon crossfertilize and destroy them. The Trust solicited help from the Daffodil Society and formed a plan to stop this invasion and to protect these flowers that mean so much to that area and to people from all over the world. At the time, the National Trust declared, “The wild daffodils are an historic feature of Ullswater, a living link back to the times when William Wordsworth roamed the valleys.”

I N PRESERVING ITS PROPERTIES, the National Trust has to cope and deal with urban expansion and environmental concerns of the day. The Trust handles this through its deep commitment to education, which is at the heart of everything it does. It offers programs to teach people about the importance of the environment and the preservation of their heritage for future generations.

An exciting new partnership and one that is quite timely is the relationship that the National Trust has entered into with npower, an energy company in the United Kingdom. Together they are creating National Trust Green Energy, a program dedicated to renewable energy sources and carbon saving measures that will enable consumers to “go green” in their own homes.

Under this program, npower will contribute £15 to a National Trust Green Energy Fund for each of its consumers every year. Meanwhile, the National Trust will be able to use these funds to initiate energy-saving programs at its various sites.

Membership in the National Trust offers free entry to all its public properties, including its historic houses and gardens, about 700 miles of coastline and 250,000 hectares of countryside (1 hectare is 2.47 acres). Members receive a handbook featuring all the Trust properties as well as regular issues of its colorful magazine.

It is easy to start a membership online by going to the Trust’s Web site at www.nationaltrust.org.uk. Americans can join the National Trust directly or sign up with The Royal Oak, the United States branch of the Trust, at www.royal-oak.org.

History and Landscape: The Guide to National Trust Properties in England, Wales and Northern Ireland is a definitive guide to the holdings of the National Trust. This beautifully illustrated volume was written by Lydia Greeves and contains a foreword by HRH The Prince of Wales. After the death of his grandmother, Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, in March 2002, Prince Charles took her place as president of the National Trust.

T HE PRINCE’s ENTHUSIASM AND UNDERSTANDING of his role as president of the National Trust is summed up in the book’s foreword: “I believe I have become President at a very interesting time in the National Trust’s history as it builds on its foundation in the 19th century, its development through the 20th century and now faces the new challenges of the twenty-first.”

The National Trust continues on so the generations that follow us will be able to enjoy the natural beauty of its holdings and get a sense of the history of the past no matter where they may live or travel in Britain.

Related: May 2008